The illusion of Time – A look at quantum physics

A German version of this text (without the footnotes) is available on the science blog „Natur des Glaubens“.

„The Garden of Forking Paths is an enormous riddle, or parable, whose theme is time; this recondite cause prohibits its mention. To omit a word always, to resort to inept metaphors and obvious periphrases, is perhaps the most emphatic way of stressing it. That is the tortuous method preferred, in each of the meanderings of his indefatigable novel, by the oblique Ts'ui Pên. I have compared hundreds of manuscripts, I have corrected the errors that the negligence of the copyists has introduced, I have guessed the plan of this chaos, I have re-established - I believe I have re-established - the primordial organization, I have translated the entire work: it is clear to me that not once does he employ the word time. The explanation is obvious: The Garden of Forking Paths is an incomplete, but not false, image of the universe as Ts'ui Pên conceived it. In contrast to Newton and Schopenhauer, your ancestor did not believe in a uniform, absolute time. He believed in an infinite series of times, in a growing, dizzying net of divergent, convergent and parallel times. This network of times which approached one another, forked, broke off, or were unaware of one another for centuries, embraces all possibilities of time. We do not exist in the majority of these times; in some you exist, and not I; in others I, and not you; in others, both of us. In the present one, which a favourable fate has granted me, you have arrived at my house; in another, while crossing the garden, you found me dead; in still another, I utter these same words, but I am a mistake, a ghost.“

Jorge Luis Borges: „The Garden of Forking Paths“ (Learn more)

If you find this text as puzzling – and beautiful – as I do, then you are well-prepared for what comes next. I'll return to the text later.

With this blog post, I want to conclude the small series on time and physics – now with a focus on quantum physics. The topic is immensely complex, and I can only sketch a few aspects here. My modest goal is to familiarize you with central ideas of quantum mechanics and to remove the hesitation for people without a background in physics to engage with this field. The guiding question is: what new perspectives emerge for our understanding of time? Again, I can only offer a preliminary assessment. To address the topic in depth would exceed the scope of this interdisciplinary blog and would require advanced knowledge of the current state of research on quantum gravity, which I do not possess (Learn more).

But one step at a time – let us proceed linearly through time ...

Light as a wave …

As described in the blogpost about relativity (in German), light is an electromagnetic wave that propagates through space at a constant speed. This is a key starting point for Einstein's Special Theory of Relativity. The famous double-slit experiment illustrates the wave nature of light: when two closely spaced slits are illuminated, an interference pattern appears on a screen behind them—a pattern of alternating dark and bright stripes. Interference can only arise from the superposition of waves that either amplify or cancel each other at specific points, depending on whether they are in phase or out of phase at those locations (Learn more).

Max Planck and the invention of quanta

The physicist Max Planck (1858–1947) studied the radiation of so-called 'black bodies' in the 1890s. A black body absorbs radiation completely, with its emission depending solely on its temperature. An example of this is the sun, which—despite its brightness—fits these conditions quite well. However, Planck encountered a paradox: according to his calculations, a black body would emit an infinite amount of energy at shorter wavelengths (in the ultraviolet range), a problem known as the „ultraviolet catastrophe“. Planck resolved this issue by proposing that energy is not transmitted continuously but rather in discrete packets—called quanta. In doing so, he introduced a constant into his equations, which is now known as „Planck’s constant“ (Learn more).

The introduction of this constant was initially a kind of „mathematical trick“ to reconcile the radiation law with experimental results. However, it turned out that Max Planck had discovered a fundamental property of nature.

And Einstein again: The photoelectric effect

Albert Einstein (1879–1955) expanded Planck’s concept by explaining the photoelectric effect (original paper) (Learn more).

He demonstrated that the energy of electrons ejected from a material by light depends on the frequency of the incoming light, not its intensity. Einstein postulated that light consists of particles, called photons, whose energy is determined by the product of the frequency and Planck’s constant (Learn more).

Although light, as we’ve seen, also exhibits wave properties, the exchange of energy between light and matter always occurs in discrete „packets of energy“—the quanta.

This discovery contradicted the classical wave theory of light and pointed to its dual nature. Robert Millikan (1868–1953) experimentally confirmed Einstein’s hypothesis in 1916, despite his initial skepticism. Einstein was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1921 for this work—not for his theories of relativity.

Incidentally, the aforementioned double-slit experiment can also be conducted with such a low intensity of light that—according to the „light as particles“ perspective—only individual photons pass through the slits at a time. In this case, the pattern on the screen gradually builds up from individual „hits“ but ultimately forms an interference pattern that cannot be explained by particles alone (Learn more).

If the experiment is extended to determine which slit the photons passed through (the so-called „which-path experiment“), the interference pattern disappears (Learn more).

Thus, light exhibits both the properties of waves and the properties of particles. This puzzling phenomenon is referred to as the „wave-particle duality“.

Particles of matter as waves …

In 1924, the physicist Louis de Broglie (1892 – 1987) proposed that wave-particle dualism also applies to matter. For example, electrons can show properties of waves and can be assigned a „De Broglie wavelength“ (Learn more).

The double-slit experiment is proof of this: If individual electrons are sent through two slits, an interference pattern is created on a detector behind the slits - typical of waves (Learn more).

According to a survey conducted by the journal „Physics World“ in 2002, the double slit experiment on electrons is considered the „most beautiful physics experiment of all time“](https://www.unimuseum.uni-tuebingen.de/de/infos/news/wie -beautiful-knowledge-creates-and-makes-famous). It shows that quantum objects appear like particles or waves, depending on the experiment. Particularly fascinating: If the gap through which the electron flies is measured, the interference pattern disappears. This makes it clear that quantum objects are not particles and waves at the same time, but rather their nature appears to depend on experiment (Learn more).

Wave function and superposition

In the 1920s, Erwin Schrödinger (1887 - 1961) developed the concept of the wave function, which provides probabilities for measurable properties of a particle such as position or spin - the latter a kind of „sense of rotation“ for which there's no equivalent in our everyday life, but which in magnetic fields can be measured (Learn more). The Schrödinger equation describes the behavior of the wave function over time. Quantum objects can exist in superposition states where they are in multiple states at the same time, e.g., in different locations or with different spins.

In the double slit experiment one can speak of a superposition in the following sense: An electron - as long as it remains „unobserved“ - „passes through both slits at the same time“, or to be more precise: exists in a superposition of states, where its path is undetermined until measured. This creates an interference pattern (Learn more)).

However, if it is measured which slit the electron goes through, the wave function and the superposition „collapse“ - according to the conventional „Copenhagen interpretation“ of quantum mechanics - and the resulting interference pattern disappears. This means that the system transitions to a state in which a physical quantity has a unique value. This process is random: the result of a measurement can only be predicted with probabilities, not with certainty. So what we're talking about here is an intrinsic coincidence that is inherent in nature and that is not related to the fact that we, as observers, simply don't know enough about the system to make firm predictions. This means that at least since the discovery of quantum mechanics, the „Laplace demon“ (see also blogpost about thermodynamics (in German) faces significant difficulties.

The Copenhagen interpretation distinguishes between the „quantum world“ (with the overlays typical of the microcosm) and the „classical world“ (with clear measurements, e.g. for location). This difference is perceived as problematic because it implies a break between the microscopic and macroscopic worlds, as if different natural laws apply there.

The decoherence theory offers a solution, which explains the transition to the classical world through the interaction of a quantum system with its environment.

In order to understand it, we have to get to know another term from quantum mechanics, that of entanglement.

Quantum entanglement

Entanglement is a phenomenon in quantum physics in which two or more particles form a common quantum state that cannot be described as a combination of the individual states. A measurement of one of the particles immediately determines the state of the other - regardless of the spatial distance between the particles. Example: Two electrons can be entangled with each other so that their spins always point in opposite directions. If you measure the spin of one electron, the orientation of the spin of the other electron is automatically determined (Learn more).

Entanglement correlations persist even when the measurements are so far apart and so fast that interaction between the particles is impossible. Entangled particles can no longer be viewed independently. In the famous EPR thought experiment, this phenomenon was questioned by Albert Einstein, Boris Podolsky and Nathan Rosen in 1935 (Learn more).

The quantum entanglement of two subsystems remains until a measurement is made on one of the systems. The common wave function „collapses“ and the states of both particles are fixed – regardless of their distance. This process is instantaneous (Learn more), but does not transmit any information faster than light, therefore does not constitute a violation of the principle of the speed of light as the maximum transmission speed. After the measurement, the particles are in defined individual states and are no longer entangled. The nature of this non-local correlation tests our understanding of space, time and causality.

The Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded in 2022 for work on the topic of entanglement. Anton Zeilinger's team, for example, managed to maintain and measure the state of an entangled pair of photons over a distance of 143 kilometers (Learn more).

Decoherence and the transition to classical behavior

Interference patterns, as described above, arise when waves are coherent, meaning they have a fixed phase relationship with each other. Decoherence describes the loss of this coherence.

In the double-slit experiment, an electron exhibits quantum superposition: it passes through both slit 1 and slit 2 simultaneously as long as its position is not measured. If the path is measured (e.g., using a laser), the electron becomes entangled with the photons of the laser and its surroundings. The isolation of the initially considered quantum system is lost, and one must now also take into account entanglements with the countless quantum particles in its environment. For the originally considered electron to still interfere, it would have to interfere coherently with the states of all these other subsystems. This is impossible given the enormous number of objects involved. As a result, the original interference disappears. Martin Bäker expresses this in a very illustrative way on his blog.

„The quantum state of your macroscopic object becomes quantum-mechanically entangled with all sorts of other objects, so the quantum nature does not disappear; on the contrary, it spreads across the entire environment. However, this spread prevents you from observing interference phenomena in the object itself."

Decoherence occurs not only during „measurements“ but during any interaction of a system with its environment. Macroscopic objects are constantly connected to their surroundings, preventing quantum superpositions from occurring (Learn more). Even the slightest interactions, such as those between a dust particle and the cosmic microwave background, cause objects to appear in non-superimposed, localized states (Learn more).

A remarkable feature of decoherence is its speed and ubiquity. Decoherence thus explains why we do not perceive quantum superpositions in everyday life (Learn more).

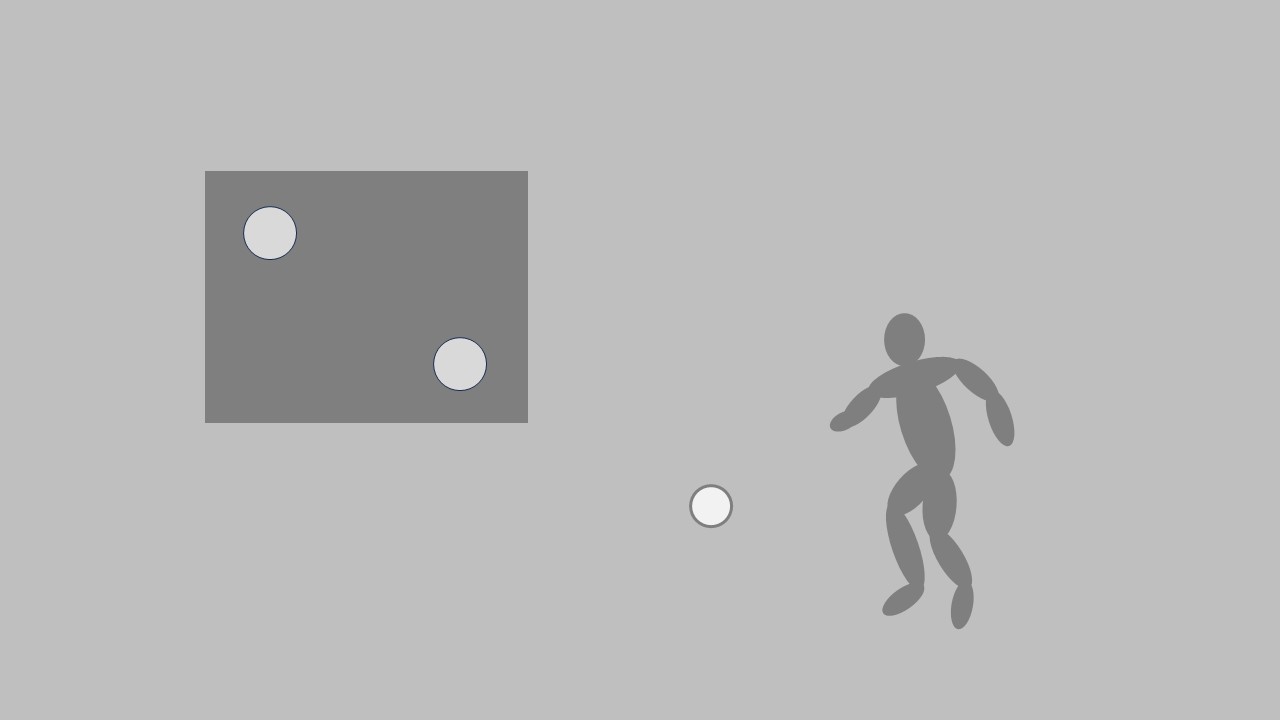

For example, a soccer ball does not exhibit quantum properties like superposition because, due to its size and complexity, it is constantly interacting with its environment. This leads to decoherence in an incredibly short amount of time, quickly destroying delicate quantum states. Additionally, the De Broglie wavelength of such an object is extremely small, making potential interference patterns undetectable.

The theory of decoherence, primarily developed by Heinz-Dieter Zeh (1932–2018), demonstrates how the quantum world transitions into the classical world without requiring additional assumptions. Classical behavior is not an inherent property of objects themselves but rather an emergent phenomenon that arises due to decoherence. Interestingly, it is the very interaction with the environment, which leads to entanglement—a phenomenon unique to quantum mechanics—that causes the emergence of classical behavior (Learn more).

A note on esoteric interpretations: Quantum mechanics is often invoked to explain mystical phenomena like „telepathy", which is scientifically unfounded. Humans consist of an unimaginably large number of molecules that constantly interact with their surroundings, causing quantum effects to quickly disappear due to decoherence (see this article in the „Standard“ (in German) on the topic).

The idea that the brain functions like a quantum computer has also been debunked. Studies show that decoherence in the brain occurs much faster than neural processes take place, meaning the brain must be regarded as a classical system. The decoherence time scales in our brain (approximately $10^{-13}$ to $10^{-20}$ seconds) are much shorter than the relevant time scales of neural processes (around 0.001 to 0.1 seconds) (Learn more) (Learn more).

Decoherence and the arrow of time

Decoherence is considered an irreversible process. There are approaches to understanding this in analogy to the rrow of time in thermodynamics through the concept of entropy.

In the study The Decoherent Arrow of Time and the Entanglement Past Hypothesis, the authors propose introducing entanglement entropy. This measures the degree to which parts of a quantum system are entangled and quantifies the shared information between these parts. Low values indicate largely independent parts, while high values indicate strong connections between them.

The authors argue that this measure could be crucial for understanding the direction of time in the universe. They postulate that the entanglement of a system with its environment increases over time, ultimately leading to decoherence—the transition from quantum mechanical to classical behavior.

One hypothesis of the study is that the universe began in a state of very low entanglement entropy. The authors justify this by suggesting that without this assumption, different parts of the wavefunction could become coherent again. This would undo past measurement results—a concept that contradicts our experience (Learn more).

The authors speculate that the increase in entanglement entropy could give time a direction, similar to how thermodynamic entropy defines the arrow of time. However, these ideas are still the subject of active research and require further validation (Learn more).

„Many-worlds“ interpretation by Hugh Everett

In 1957, Hugh Everett (1930–1982) published his „Relative State“ theory, which later became known as the „Many-worlds“ hypothesis. Everett proposed that the state of a quantum system must always be considered relative to an observer or another system, with the observer becoming part of the superposition..

Unlike the Copenhagen interpretation, which assumes a collapse of the wavefunction upon measurement, Everett's hypothesis suggests that the observer's state splits into a superposition of different states with each measurement, representing all possible outcomes. However, the observer perceives only one of these states, while the others remain invisible to them. This idea was later developed, especially by Bryce DeWitt (1923–2004), into the concept of branching parallel universes (Learn more) (Learn more).

With the theory of decoherence, Everett's hypothesis gains significant support: every interaction between a system and its environment can now be seen as a „measurement“ or „observation“ leading to a branching of „reality“. The more strongly a system interacts with its environment, the more frequently such branchings occur. In this way, decoherence creates different branches, each representing one realization of the original superposition. This implies that the „universe“ splits an unimaginable number of times—practically constantly (Learn more).

Although all branches continue to coexist on a universal level, the system appears to the observer to adopt a well-defined state because the quantum information is distributed across many subsystems through these interactions. Other branches are imperceptible because interference between them vanishes. This creates the impression of randomness, even though the universal wavefunction evolves deterministically. Randomness here is not a fundamental property of the universe but a result of the many parallel realities arising from quantum mechanical processes.

This hypothesis is philosophically exciting, but is met with criticism because it is not falsifiable. Parallel worlds can neither be observed nor proven experimentally (Learn more).

A literary parallel to this theory can be found in Jorge Luis Borges' novella „The Garden of Forking Paths“, from which I quoted at the beginning. Interestingly, this work appeared long before Everett's hypothesis. Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker (1912 – 2007) points out in his book „Aufbau der Physik“, dtv 1988, p. 564f, that the structure of the novella is surprisingly close to the many-worlds interpretation (Learn more):

For an observer, „the world narrows down to everything that follows from the one measurement result he perceives. For him it must seem as if there is only this one branch of the world (…) For the theorist (…) the world has thus split into many non-communicating but co-existent 'worlds' as there are possible measurement results. And so in infinitum.“ (Learn more)

The „time problem“ in quantum mechanics

To conclude, I would like to briefly address another aspect of the topic of time that arises from the efforts to unify general relativity (GR) and quantum theory into a theory of quantum gravity. As previously mentioned, I cannot provide a comprehensive account of the „time problem“, as that would require extensive experience in the field of quantum gravity, which I do not possess. However, I would like to offer a few insights (Learn more).

In GR, time is a dimension of spacetime, where time intervals—i.e., the duration between events—are influenced by masses. A notable example of this is gravitational time dilation. In contrast, in quantum mechanics, time is a parameter in the Schrödinger equation and not a measurable quantity like position or momentum. This fundamental difference makes it challenging to provide a unified description. The discrepancy complicates efforts to merge the two theories into a single coherent framework.

An intriguing approach comes from William K. Wootters and Don Page, who proposed in 1983 that time is not a fundamental phenomenon but rather emerges from quantum mechanical correlations between systems. Similar to Everett's interpretation, their approach also considers „relative“ states, assuming that the observer and their interactions with the „rest of the world“ must be regarded as part of the system.

In their model, the universe is static. Within, a part of the universe can serve as a „clock“ that describes changes in another part. Each „clock time“ corresponds to a „relative state“ of the universe, interpreted from the perspective of the clock.

While the original Page and Wootters article from 1983 does not directly address quantum entanglement, this concept has emerged as a central element in later discussions. In a paper from 1984 Wootters writes explicitly about „non-local correlations“ and refers to the original paper from 1935 on the EPR paradox mentioned above (Learn more).

The idea can be simplified as follows: time is not absolute, but is created by the relationships between the parts of a system.

Experiments support this approach: In a 2013 experiment, two entangled photons were used. One photon served as a „clock“ while the other represented the rest of the universe. To an „inner“ observer connected to the clock photon, the second photon appeared to change. However, an „external“ observer who looked at the entire system found that it remained static.

The result shows that while the universe as a whole appears unchanged, the perspective of an inner observer creates the illusion that time is passing. This supports the hypothesis that time is not a fundamental property of the universe, but rather an emergent phenomenon arising from quantum entanglement.

Conclusion

Our understanding of time is challenged and shaped in various ways by thermodynamics (in German), relativity (in German) and quantum mechanics:

Thermodynamics: The second law of thermodynamics describes the continuous increase of entropy in closed systems, which explains the direction of time („arrow of time“) and the irreversibility of thermodynamic processes. Systems tend toward states of higher entropy but do not spontaneously revert. This could make the uniqueness of time and the phrase „time does not repeat itself“ plausible.

Relativity: Time is not an absolute quantity but depends on the frame of reference and is intertwined with space into spacetime. In General Relativity, time is part of the curved spacetime influenced by mass and energy. Time emerges from the structure of the universe. The expansion of the universe also supports a non-cyclical flow of time.

Quantum Mechanics: In the microcosm, the laws of nature appear to differ from those in everyday life (the macrocosm). Phenomena such as superposition and entanglement seem counterintuitive but are crucial for understanding decoherence. Decoherence, in turn, an irreversible process, allows classical behavior to emerge from the quantum world and gives time its direction. Additionally, quantum mechanics suggests that randomness is a fundamental aspect of nature. This randomness manifests in an open future, while the many-worlds interpretation portrays a deterministic evolution where, nonetheless, for each „branch“, the future remains uncertain, governed in a sense by chance.

Efforts to unify general relativity with quantum theory in quantum gravity suggest that time is not a fundamental property of the universe but rather emerges for us as „internal observers“. Our experience of the flow of time may merely be an illusion arising from our position within the universe. On a fundamental level, the universe might even be timeless, which would have far-reaching consequences for our understanding of the cosmos and reality. Time could be an emergent phenomenon, arising from quantum entanglements and interactions between systems.