The Night Sky as a Common Good - why It won't be dark at night anymore (soon) - 2

A (shorter) German Version of this blog series can be found on the German science blog „Natur des Glaubens”: Der Nachthimmel als Gemeingut.

„Before we invented civilization our ancestors lived mainly in the open out under the sky. Before we devised artificial lights and atmospheric pollution and modern forms of nocturnal entertainment we watched the stars. There were practical calendar reasons of course but there was more to it than that. Even today the most jaded city dweller can be unexpectedly moved upon encountering a clear night sky studded with thousands of twinkling stars. When it happens to me after all these years it still takes my breath away. In every culture, the sky and the religious impulse are intertwined. I lie back in an open field and the sky surrounds me. I’m overpowered by its scale. It’s so vast and so far away that my own insignificance becomes palpable. But I don’t feel rejected by the sky. I’m a part of it – tiny, to be sure, but everything is tiny compared to that overwhelming immensity. And when I concentrate on the stars, the planets, and their motions, I have an irresistible sense of machinery, clockwork, elegant precision working on a scale that, however lofty our aspirations, dwarfs and humbles us.” (Learn more)

The experience of a starry sky is one that humans have shared for millennia (Learn more). What impact would it have if the appearance of the naturally dark night sky – with its seemingly countless stars visible to the naked eye and the bright band of the Milky Way – were to be impaired? What happens to us humans if this experience is irretrievably lost for a large part of the Earth's inhabitants? What then happens to parts of the animal and plant world?

Light pollution from terrestrial light sources

The experience of the natural night sky is increasingly being disrupted by artificial human-made light sources, a phenomenon also known as „light pollution“. The term „artificial light at night“ (ALAM) is also common. The largest contributors to this are the lights of our cities and the light emitted during other activities, such as driving at night.

The following photo was taken on the Hornisgrinde in the Black Forest, Germany, at an altitude of 1150 meters above sea level.

In the sky, just to the left of the center of the image, the constellation Orion is prominently visible. Additionally, a very special planetary alignment is depicted: in the upper left of the image is Jupiter, near the horizon on the right is the setting Venus, and directly above it is Mars.

The lower part of the image is characterized by many different human-made light sources. On the right, the lights of villages in the adjacent Black Forest valleys shine through the fog in a yellow color, while the artificial lights in the background on the right come from the densely populated Rhine Valley. On the left side of the image, the floodlights of nearby ski lifts emit a bright bluish light into the sky. Further left (no longer in the image), the light from another ski lift scatters in the atmosphere, significantly impairing the view of the starry sky. The light even reflects off the snow at my photo location, several kilometers away. Incidentally, the ski lifts are located directly next to the Black Forest National Park.

„Light pollution is one of the most pervasive forms of environmental alteration. It affects even otherwise pristine sites because it is easily observed during the night hundreds of kilometres from its source in landscapes that seem untouched by humans during the day, damaging the nighttime landscapes even in protected areas, such as national parks.“ (Learn more)

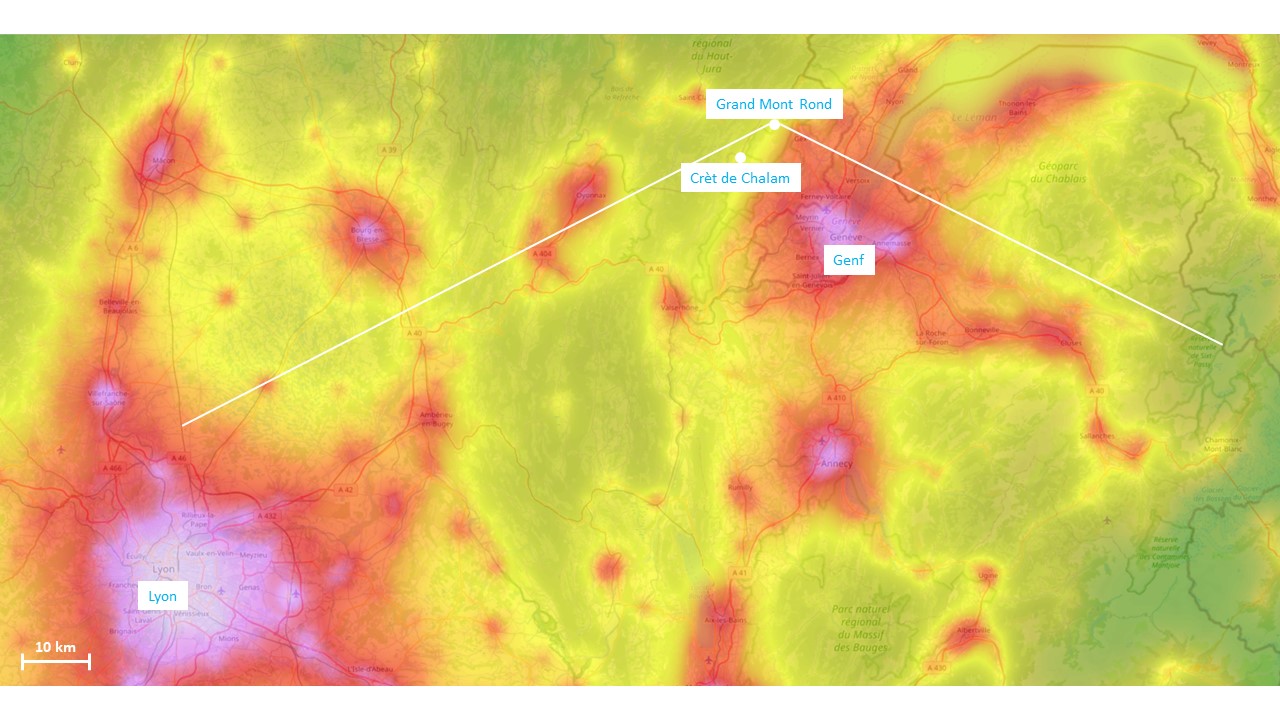

The following photo provides a good impression of how far light pollution from urban areas can extend spatially. Here, the effect is further amplified by high cirrus clouds that reflect the light. The photo was taken near the Grand Mont Rond in the French Jura, at an altitude of approximately 1600 meters above sea level.

The photo was taken in a southerly direction. The lights shining from below the fog at left belong to the metropolitan area of Geneva, in a distance of about 20 kilometers. The dark mountain silhouette in the center of the image is the range of Crêt de la Neige, the highest peak in the Jura mountains. The artificial lights at right reflected by the clouds originate from the metropolitan area of Lyon more than 100 kilometers remote (Learn more).

The following photo shows how a very nearby urban area influences nocturnal landscape photography. It was taken on a clear winter night on the Grand Ballon, the highest peak of the Vosges Mountains at about 1400 meters above sea level, facing east. The mountain massif borders directly on the densely populated Alsace region, and one looks down from above on the Colmar area. The image may have an aesthetic appeal, also and especially because of the anthropogenic light sources beneath the fog, but it also demonstrates how dramatically our civilization has altered the night sky. This panorama is composed of several individual shots taken consecutively with the same exposure time.

Using artificial light creatively in night landscape photography

I would like to demonstrate with a photo how artificial light sources can be creatively integrated into night landscape photography.

The following photo was taken in the northern Black Forest, Germany, at an altitude of 1000 meters and shows the view northward towards the densely populated Rhine plain, including the metropolitan area of Karlsruhe. I deliberately chose this location so that an area with a lot of artificial light – combined with well-recognizable mountain silhouettes – can be seen on the horizon.

The main subject of the picture is the comet „Neowise“ (top left), which was visible in Europe during the summer of 2020. I intended to show the comet with a regional context. Therefore, I chose this location for the shot. Since the entire mountain landscape to the north is significantly lower than my observation point, you can get a particularly good view of the foothills of the Black Forest and the Rhine plain behind it. Locals familiar with the area can recognize the individual towns and mountain peaks. The photo was also printed in a regional daily newspaper; for residents of this area, it was likely interesting to learn that they could observe the comet from their „home“.

Another photo that would simply not „work“ without the presence of artificial light, is the following one. It was taken also in the Northern Black Forest near Baden-Baden during inversion weather conditions. Locals will recognize the mountain and the village as well in the previous picture with the comet in the background.

Atlas of light pollution

If you want to find out which regions on Earth are particularly affected by artificial light in terms of experiencing the night sky, and in which areas you can still enjoy an unobstructed night sky, there is now plenty of information available online. I will highlight a few of these resources.

For many years, satellites have been detecting artificial light sources on Earth. In 2011, the „Suomi National Polar-Orbiting Partnership (NPP)“ satellite was launched, which carries a radiometer for the visible and infrared range (Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite, abbreviated: VIIRS).

The data is published by NASA under the keyword „Black Marble“ (Learn more). The same data forms the basis for an online version of the „light pollution map“ (Learn more). A world atlas of light pollution published in 2016 uses VIIRS data (Learn more).

„This atlas shows that more than 80% of the world and more than 99% of the U.S. and European populations live under light-polluted skies. The Milky Way is hidden from more than one-third of humanity, including 60% of Europeans and nearly 80% of North Americans. Moreover, 23% of the world’s land surfaces between 75°N and 60°S, 88% of Europe, and almost half of the United States experience light-polluted nights.“

One could say that a third of humanity lives in places where the Milky Way can no longer be seen.

Satellites, whose data form the basis for the aforementioned light pollution map, can measure light emitted upwards. However, they do not provide information about horizontally emitted light. Therefore, they can only partially represent the light pollution perceived from Earth. A study (Learn more) involving citizen scientists who were asked to assess the degree of light pollution at their location can supplement the satellite data. This study concludes that in recent years, the brightness of the night sky has approximately doubled every eight years.

One might think that in the still „dark“ areas far from urban lighting, one can enjoy an unobstructed starry sky. Unfortunately, this is not the case, as there are other sources of interference that are not located on the Earth's surface: airplanes and satellites. Photographers who take long series of images of the night sky, for example, for time-lapse shots, may not be too pleased about this.

Go to part 3 of the blog series

Go to previous part of the blog series